Maximilian M. Mueller, M.D., Valentin Hingsamer, Sebastian Conner-Rilk, M.D., Tatiana C. Monteleone, B.S., Robert J. O’Brien, Dr.P.H., M.H.S., P.A.-C., and Gregory S. DiFelice, M.D.

From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York-Presbyterian, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York, U.S.A. (M.M.M., V.H., S.C-R., T.C.M., R.J.O., G.S.D.); Department of Trauma Surgery, Orthopaedics and Sports Traumatology, BG Klinikum Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany (M.M.M.); Department of Orthopedics and Trauma-Surgery, Division of Trauma Surgery, Medical, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria (V.H.); Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria (S.C-R.); OCM – Orthopedic Surgery Munich, Munich, Germany (S.C-R.,); and Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (R.J.O.).

Received August 15, 2025; accepted September 14, 2025.

Address correspondence to: Gregory S. DiFelice, M.D., Hospital for Special Surgery, East River Professional Building, 523 East 72nd St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10021, U.S.A. E-mail: difeliceg@hss.edu

© 2025 THE AUTHORS. Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the Arthroscopy Association of North America. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

2212-6287/

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eats.2025.103953

Abstract

In this Technical Note, we present the surgical technique for primary arthroscopic repair of chronic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. This approach is indicated for proximal type I and II ACL tears with good-to-excellent tissue quality, characterized by an intact synovial sheath and a simple rupture pattern. Compared with acute ACL primary repair, the most significant challenge lies in the careful mobilization and preparation of the scarred ACL remnant. Notably, chronic ACL tears often present with tissue remnants scarred to the posterior cruciate ligament and/or the femoral notch wall, which may still show favorable tissue quality. With meticulous surgical technique and appropriate patient selection, primary arthroscopic repair of chronic ACL tears may therefore remain a viable option beyond the acute phase. Ultimately, tear location and tissue quality should be the primary determinants for selecting ACL primary repair.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) preservation techniques.1-11 Anterior cruciate ligament primary repair (ACLPR) is primarily indicated for proximal, modified Sherman type I or Il tears with good-to-excellent tissue quality. 12-14 To avoid deterioration of the ligament remnant, which could compromise repairability and potentially increase the risk of failure, 15-17 ACLPR is generally recommended in the acute setting, typically within 28 days of injury.

However, several studies have reported low failure rates and favorable clinical outcomes even when ACLPR is performed in the chronic setting. 2, 15,18-20 The need for delayed repair may result from delayed diagnosis,21,22 administrative delays, 12,23,24 or after an diagnosis, initial nonoperative approach when persistent instability necessitates surgical intervention. 5,26 Importantly, chronic ACL tears often present with remnants scarred to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and/or the femoral notch wall27 yet may retain good-to-excellent tissue quality. In this Technical Note, we present the surgical technique for primary arthroscopic repair of chronic ACL tears, which builds upon the established anatomic biologic ACLPR technique28 to enable safe and effective primary repair of select cases in the chronic setting.

Surgical Technique

Indications

This Technical Note presents the chronic arthroscopic ACLPR technique (Video 1). Indications are outlined in Table 1 and are determined on the basis of the ACL Preservation First treatment algorithm. 29 Key criteria include a proximal, type I or II tear, good-to-excellent tissue quality with a simple rupture pattern, and at least 50% preservation of the synovial sheath. 12,28 Although surgical intervention within the first 4 weeks after injury is generally recommended,12 delayed presentation should not be regarded as an absolute contraindication for ACLPR. 15

| Indications | Absolute Contraindications |

| Proximal type I or type II ACL tears | Type M-V ACL tears |

| Good-to-excellent ACL tissue quality, defined by simple tear pattern and >50% pre-served synovial sheath | Poor and fair tissue quality |

| Full-thickness and partial tears | Insufficient remnant length |

| Isolated ACL injuries and ACL injuries in multi-ligamentous knees | <50% remaining tissue (cross-section) |

Table 1: Indications and Absolute Contraindications of Chronic ACLPR

Intraoperative Indication

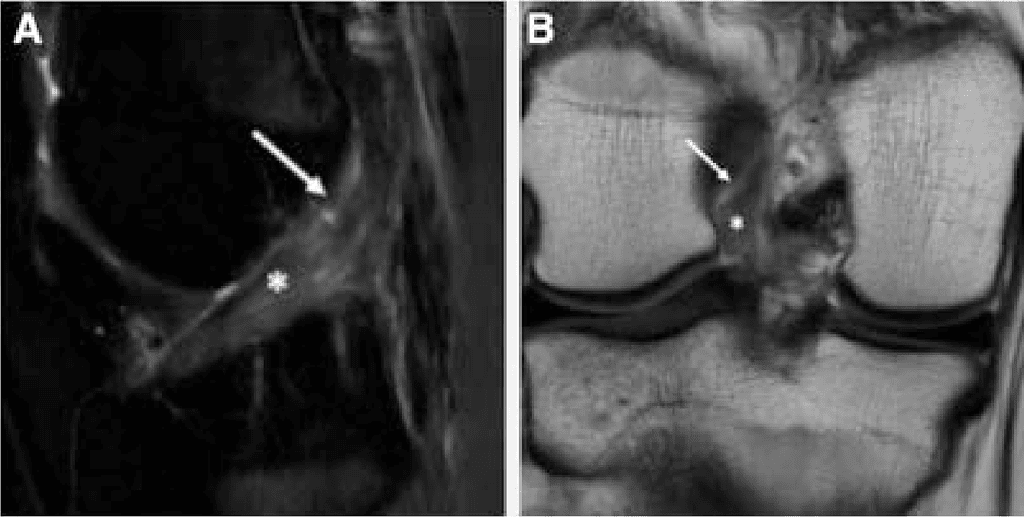

Because magnetic resonance imaging does not always allow accurate and final assessment of tear location (Figure 1) and tissue quality, diagnostic arthroscopy is recommended before determining the definitive treatment approach (ACLPR vs anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [ACLR]). Standard anterolateral and anteromedial (AM) portals are first established. After treatment of concomitant pathologies, both tear location 13,30 and tissue quality24 are assessed.

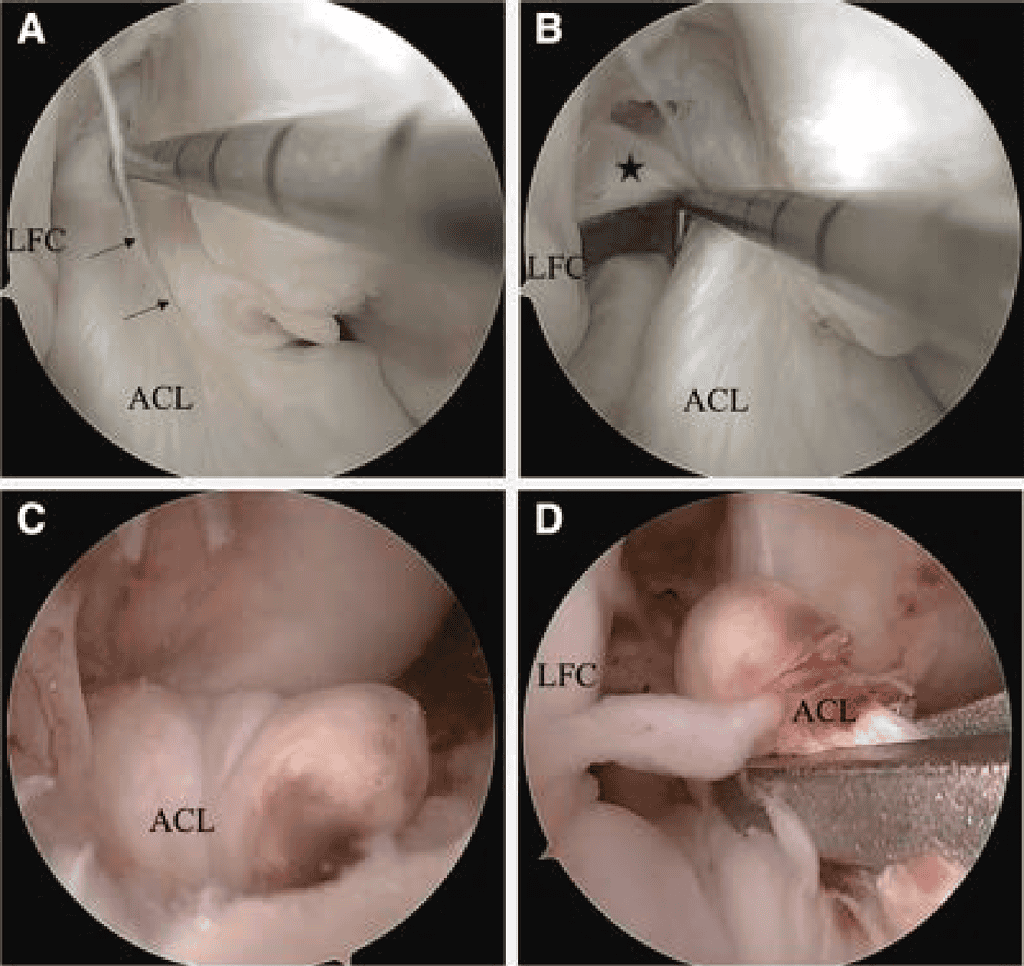

In chronic cases, 2 principal intraoperative scenarios are commonly observed (Figure 2): (1) ACL remnant scarred to the PCL and/or femoral notch wall: The ACL remnant is scarred to the PCL and/or notch wall. In this scenario, the ligament can often be carefully dissected free. Although the anterior fibers may appear insufficient in length to reach the femoral footprint, a substantial portion of viable tissue is frequently found scarred posterior to the PCL. With meticulous dissection, this tissue can often be mobilized sufficiently to allow anatomic refixation. (2) Anterior displacement of the ACL remnant: A substantial portion of the ACL is displaced anteriorly. Although the ACL remnant may be mobilizable, the tissue quality is frequently poor, and the ACL stump often cannot be adequately reduced to the femoral footprint. In these cases, anatomic ACLPR with biologic scaffold augmentation,31 all soft-tissue autograft augmentation32 or ACLR is indicated depending on the volume of tissue remaining.

Assessment of Tissue Quality

Tissue quality can be described on the basis of rupture pattern and synovial sheath integrity (Figure 2). 24 Rupture patterns are categorized into 3 grades: grade 1, one-strand, grade 2, two-strands, and grade 3, complex tear.24 Synovial sheath integrity is classified as completely intact (grade 1), more than 50% intact (grade 2), and less than 50% intact (grade 3).24

Separation of ACL and PCL

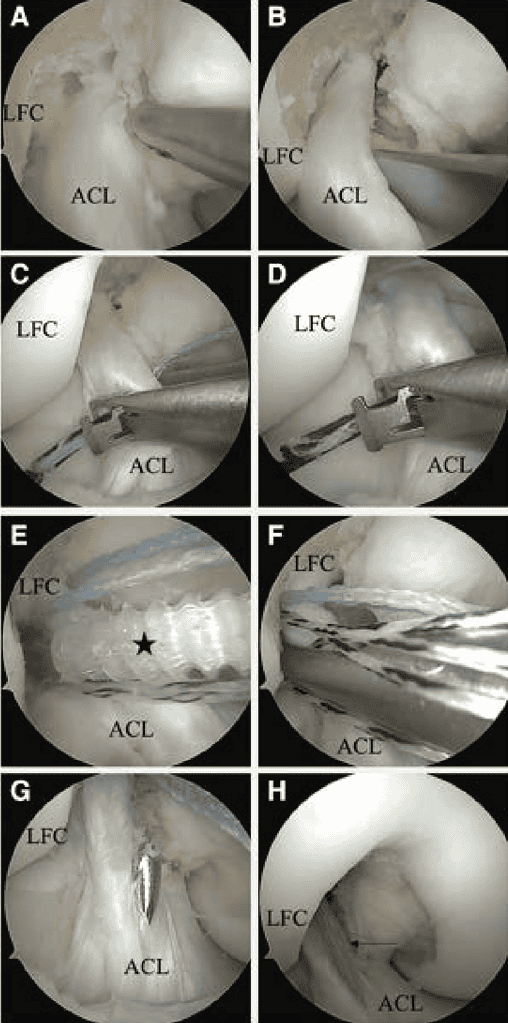

When ACLPR is indicated and the ACL remnant is found to be scarred to the PCL, careful separation of the 2 structures is required (Figure 3 A and B). The detachment should be initiated using arthroscopic scissors, with primary attention directed toward avoiding injury to both the ACL and PCL. The ACL remnant can often be further mobilized using a blunt probe, minimizing iatrogenic trauma to the ligament. Dissection can be particularly challenging in the posterior portion; however, complete mobilization is essential to enable anatomic refixation. Nevertheless, partial residual scar tissue may be tolerated as long as the remnant can be adequately reduced to the anatomical femoral footprint. It the ligament frays to an extent that intraligamentary suture placement becomes unfeasible, ACLPR should be abandoned in favor of autograft augmentation or reconstruction depending on remaining remnant (Table 2).

Anatomic Double-Suture Anchor Repair

A soft cannula can be inserted through the AM portal to facilitate suture management. Arthroscopic, anatomic, biologic ACLPR is performed, using OSSIOfiber suture anchor fixation (OSSIO Inc) and ActivBraid Collagen Co-Braid Sutures (Zimmer Bio-met) to reduce the synthetic “burden” of the procedure, as described previously. 28,33,34 Both ACL bundles are sutured with No. 2 ActivBraid Collagen Co-Braid Sutures using a Bunnell-type pattern with a self-retrieving suture passer (Figure 3 C and D). Gentle tension is maintained on the extracapsular ends of the repair sutures via the AM portal during each stitch to counteract the force of the piercing suture passer. It resistance is encountered while advancing a repair suture, the needle should be repositioned to prevent inadvertent transection of previously placed sutures. An accessory inferomedial (IM) portal is established to facilitate suture management and achieve a better approach angle for the later placement of the femoral suture anchors. Final sutures should exit the ACL proximally in a way to optimally reduce the ACL to the femoral wall. In this way, while the AM repair sutures may exit lateral and medial of the ACL, the PL repair sutures should exit proximally on the lateral side.

| Pitfalls | Pearls |

| Fraying of ligament tissue due to prolonged suturing. | Careful manipulation of the tissue. |

| Overestimation of the amount of preservable tissue. Not specific to chronic ACPR: | Consideration of biologic scaffold or autograft augmentation. |

| Transection of previously placed repair sutures. | Monitor resistance when placing sutures. |

| Poor suture management. | Create a low IM portal and use a cannula in the anteromedial portal. |

| Breaking the suture passer’s needle by impacting the lateral femoral condyle. | Rotate hand holding the suture passer downwards to avoid impacting the needle. |

| Posterior femoral condyle suture anchor perforation. | Optimize angle for suture anchor placement by using the IM portal and deploy anchors in 90° flexion for the AM and 115° in case of the PL. |

| Overconstraint of the knee through fixation of the suture augmentation in flexion. | Full ROM cycling of the knee before tensioning and fixing the suture augmentation near full extension. |

Table 2: Pitfalls and Pearls of Chronic ACLPR

A limited notchplasty is performed anteriorly to the femoral ACL footprint using a shaver to induce bleeding. At 115° knee flexion using the accessory IM portal, a 4.5-x 20-mm hole is punched and tapped at the PL bundle’s anatomical origin before tensioning the PL repair sutures with a 4.75-mm biointegrative OSSIOfiber suture anchor that is placed in standard fashion (Figure 3E). After adequate placement is confirmed, the core sutures are passed from lateral to medial through the proximal PL bundle and then parked out the accessory IM portal (Figure 3F). The AM suture anchor is placed at the AM origin with the knee at 90° flexion, pre-loaded with the AM repair sutures and an additional suture augmentation (2.5-mm ActivBraid Collagen Co-Braid Tape). At this point, the core sutures from the PL anchors are tied down tight using a knot pusher to place 3 to 4 alternating half hitches. Finally, the augmentation sutures are passed through a 2.4-mm tibial drill hole at the anterior one third of the distal ACL footprint and tensioned independently in full extension with a final OSSIOfiber anchor to avoid over constraint of the knee (Figure 3 G and H).

Rehabilitation

Full weight-bearing and unrestricted passive range of motion as tolerated is allowed in the immediate post-operative period. In cases in which a concomitant meniscal repair is performed, weight-bearing is restricted to toe-touch, with range of motion limited to O to 90° for up to 4 weeks. A hinged knee brace locked in full extension is recommended for the first 2 to 4 weeks to prevent buckling. Once protective quadriceps function is restored, the brace is gradually unlocked and weaned until unrestricted ambulation is achieved.

Discussion

Two mechanisms may hinder chronic primary repair of the ACL: Deterioration of tissue quality and/or retraction of the ligament. O’Donoghue et al. observed in a porcine model in 1966, that ACL tissue quality may deteriorate over time.15-17 The intact synovial sheath protects the ACL from degradative effects of the synovial environment.35,36 If the synovial sheath-and with it, the periligamentous capillaries it contains-is injured, healing capacity may potentially be reduced. 37 This effect may contribute to a greater failure rate as reported after dynamic intraligamentary stabilization, in the case of a complex tear pattern without preserved synovial sheath integrity.38 Additionally, as a result of the prevention of clot formation, the ACL stump may retract over time.39 One reason proximal ACL tears are more likely to be repairable is that, unlike midsubstance tears, they tend to scar to the PCL. 39,40 This scarring limits retraction of the ligament stump, thereby preserving its length and alignment and maintaining the feasibility of primary repair. Lo et al.27 observed an attachment of the ACL to the PCL in 72% of patients with ACL injury. Surgical delay, as a criterion for indication, may unnecessarily exclude a substantial number of patients who could still be suitable candidates for arthroscopic ACLPR if other factors, such as a proximal tear location and sufficient tissue quality, are present. This is particularly relevant for patients who initially opt for nonoperative treatment with the possibility of delayed surgical intervention-often the result of personal preference, age, activity level, or underlying medical conditions-which is an approach that is considered reasonable in selected patient cohorts.25,26 If this nonoperative strategy fails because of persistent instability, these patients may still wish to avoid ACLR due to its associated morbidity, and may therefore be suitable candidates for arthroscopic ACLPR. The chronic arthroscopic ACLPR technique represents a modified application of the established anatomic and biologic ACLPR method. 28,33,41 The key surgical step in this approach is the careful arthroscopic detachment of the remnant using arthroscopic scissors, with particular attention to preserving ligament integrity, as the ACL tissue may be fragile and prone to fraying. Although ACLR remains the gold standard and should be pursued when tissue preservation is not feasible, the chronic arthroscopic ACLPR technique offers the advantage of avoiding autograft harvest and reducing surgical morbidity.

Disclosures

The authors declare the following financial interests/ personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: G.S.D. receives royalties, owns stock, and is a paid consultant for Zimmer Biomet; receives royalties from Arthrex; received stock options, provides consulting services, and participates in funded research with Miach Orthopaedics; and receives stock options and provides consulting services for OSSIO. All other authors (M.M.M., V.H., S.C-R., T. C.M., R.J.O.) declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.