Author: Garret Strand, DPM, Shasta Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, CA.

INTRODUCTION

Hallux Abducto Valgus (HAV) (also referred to as Hallux Valgus (HV) or Bunion) is one of the most common deformities in the foot and ankle field. This pathological condition involves malpositioning of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, caused by both a medial deviation of the first metatarsal bone and a lateral deviation and pronation of the great toe. While HAV prevalence reaches 23% in adults 18-65 years of age, it peaks to 35.7% in those older than 65 years. Females have considerably higher prevalence for the deformity1. Additional predisposing factors are family history, metatarsus adductus, first ray hypermobility, pes planus, equinus contracture, ligamentous laxity, and length of the first metatarsal1. HAV symptoms include altered joint mechanics, dysfunction, and progressive pain often at the medial eminence of the first MTP joint. This deformity can vary from mild to severe. More than 100 different operative techniques have been described for the correction of HAV, however no single procedure is universally successful in all patients with severe HAV and even technically well-performed procedures may fail2,3. While mild to moderate HAV can usually be corrected with a distal osteotomy of the first metatarsal, severe HAV deformities with subluxation of the hallux joint, hypermobility of the first tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint, or generalized laxity as well as recurrent HAV following surgical corrections, are the main indications in the literature for a corrective fusion of the first TMT joint, the so-called modified Lapidus. High union rates and high-level of patient satisfaction encourage correction using Lapidus procedure, in particular for severe HAV conditions.

CASE PRESENTATION

63-year-old, healthy female, non-smoker, with daily routine of moderate physical demands. The patient complained of left foot pain on ambulation, and difficulty with shoe gear. On examination, severe HAV clinical appearance with large deviation of the hallux laterally and hypermobility at the first TMT. The patient requested non-metal surgical fixation.

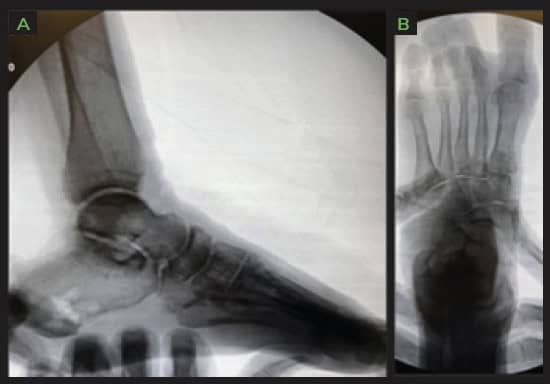

Pre-operative Planning

Weight bearing radiographs reveal severe HAV with increase in tibial sesamoid position and 1st Inter Metatarsal (IM) angle.

Surgical Procedure

First TMT joint arthrodesis, Calcaneal autograft harvest.

The following OSSIOfiber® fixation implants were used:

- OSSIOfiber® Compression Screw 3.5x28mm x 1 unit

- OSSIOfiber® Compression Screw 3.5x30mm x 1 unit

- OSSIOfiber® Compression Screw 3.5x32mm x 1 unit

Surgical Technique Steps

- Dissection / Access :

Dorsal medial 1st TMT incision, lateral release was performed with mini open incision, 1st TMT was hand prepped, and autograft was packed within joint and temporarily fixated with 0.062″ k-wires. A manual reduction was performed. - Fixation Site Preparation :

Hand preparation, fenestrated until bleeding bone was present. - Implant Insertion :

Three 3.5mm OSSIOfiber® headless Compression Screws were used, two crossing the TMT for compression, third one from M1 to M2 base to hold transverse correction due to large pre op deformity angle. - Closure

3-0 vicryl for deep and superficial closure, 3-0 nylon for skin.

Post-Operative Protocol

- Non-weight bearing: 6 weeks

- Transition to partial weight bearing: CAM boot for 6 weeks with physical therapy.

- Full weight bearing: In supportive tennis shoes after 12 weeks.

Patient Follow-up

The surgical site completely healed by the time the patient came in for the 2 weeks check-up, and sutures were removed. Swelling was minimal over the 1st TMT joint, with minimal discomfort over the joint through initial healing phase. Physical therapy started at 6 weeks post op. 1st MTP joint range of motion improved gradually with passive and active exercises. Sequent radiographs showed well maintained bone reduction and increased signs of fusion from visit to visit.

Summary:

First TMT fusions are a reliable and reproducible way to correct severe HAV deformities. Patients are more aware and involved in their medical care than ever before and the trend is moving away from using permanent hardware such as metal/plastics within the body, to a more natural fixation. Bio-integrative implants offer an excellent alternative way of fixating challenging deformities such as the one presented here, providing the required mechanical fixation strength while avoiding the need to deal with retained hardware later in life.

References

1. Ray, J. J. et al. Hallux Valgus. Foot Ankle Orthop. 4, 1–12 (2019).

2. Pinney, S., Song, K. R. & Chou, L. B. Surgical treatment of severe hallux valgus: the state of practice among academic foot and ankle surgeons. Foot ankle Int. 27, 1024–1029 (2006).

3. Fraissler, L., Konrads, C., Hoberg, M., Rudert, M. & Walcher, M. Treatment of hallux valgus deformity. EFORT Open Rev. 1, 295–302 (2016).